8 minutes

Cross-Site Request Forgery: Introduction

Cross-Site Request Forgery is a common and prolific exploit that takes advantage of sessional cookies that browsers automatically allocate to HTTP requests - and they’re the reason you shouldn’t click suspicious links, even if the URL sort of sounds legitimate.

This is a discussion on the importance of protecting against such attacks, and to demystify the unknowns that many people have about the exploit in general. I will be using my solution for two challenges I did in the past to help explain my points - the writeups for which you can consult here as well.

Let’s Begin!

CSRF attacks are exploits that trick users into unknowingly performing actions that they didn’t intend/consent to perform. They work through using your credentials without you actually knowing - through the use of automatic additions of your session ID to browser cookies in HTTP requests. How, specifically, do the CSRF exploits work?

Consider my writeup for the challenge “cookie-recipes-v2” from Redpwnctf 2020. The challenge called for us to execute multiple CSRF attacks - but the reason why we wanted to do a CSRF attack and not an XSS attack (the two are quite similar) lies in the architecture of the underlying server.

The premise of the challenge was that you could “purchase” the flag in the program if you had enough virtual credits to do so - the price for buying the flag was around 1000 credits, but when you make an account, you start with only 200 (or 100?). At first glance, there are no ways to gain more credits, and so you were out of luck. However, in the infrastructure of the application, there exists a certain API endpoint called /gift:

['gift', async (req, res) => {

if (req.method !== 'POST') {

res.writeHead(405);

res.end();

return;

}

const result = {

'success': false

};

// Get token from cookie

const cookies = util.parseCookies(req.headers.cookie);

if (!cookies.has('token')) {

util.respondJSON(res, 200, result);

return;

}

const token = cookies.get('token');

if (typeof(token) !== 'string') {

result.error = 'Invalid token';

util.respondJSON(res, 401, result);

return;

}

// Get id from token

let id;

try {

id = database.getId(token);

} catch (error) {

res.writeHead(500);

res.end();

return;

}

if (!id) {

result.error = 'Invalid token';

util.respondJSON(res, 401, result);

return;

}

// Make sure request is from admin

try {

if (!database.isAdmin(id)) {

res.writeHead(403);

res.end();

return;

}

} catch (error) {

res.writeHead(500);

res.end();

return;

}

// Get target user id from url

const user_id = util.parseParams(req).id;

if (typeof user_id !== 'string') {

res.writeHead(400);

res.end();

return;

}

[...]

This endpoint was only relevant to the admin, who they could specify a user to gift tokens to. This is a state-changing action of interest to us, a hallmark signal that a CSRF exploit is at play here. CSRFs work by carrying out relevant actions that change some aspect of the program for us - doing so whilst using the permissions of a user without that user ever authorizing.

The first few checks in the endpoint are important to focus on: in order to validate that the user calling this endpoint has admin privileges, the server extracts a token ID from the cookies that are packaged in the request - cookies that are automatically added by the client. In these cookies exist sessional-based IDs, and they help to identify a person utilizing an application. However, if this application only relies on cookie-based user verification to verify their users, CSRF vulnerabilities will occur. This seems good on paper: if you don’t have the correct token ID from the browser/client-added cookie packaged in the request, then your request will be denied, because you need the same ID as the valid user, which is only in use when the user is currently utilizing the application. However, if it’s the only form of checking that a program does, a malicious hacker can easily bypass that check. This is where the language “perform actions that the user didn’t authorize” becomes important. In a CSRF attack, you’re the one making the request, you just don’t know that you’re making it.

Back to my REDPWNCTF example, consider this webpage, crafted and hosted by a hacker:

<html>

<body>

<form action="https://cookie-recipes-v2.2020.redpwnc.tf/api/gift?id=1234567890" method="POST">

</form>

<script>

document.forms[0].submit();

</script>

</body>

</html>

When someone visits this webpage and the browser loads it, the form in the webpage is automatically constructed, and the <script> tag ensures its sent immediately. If any user who doesn’t have admin priviliges visits this webpage and makes a POST request unknowingly, their sessional id that is automatically added into the request by the browser will be extracted from their cookie by the server, and their request will be rejected. Thus, nothing will happen when we non-admin users visit. However, if an admin visits this webpage, their id that is extracted from their cookie will be validated, and the request will be accepted. All the admin did was simply visit the webpage in question - the request was sent, using the admin’s credentials without the them ever knowing or consenting. The request, once validated, will fire the endpoint and do all the necessary actions - and the user with the ID “1234567890” will be gifted credits.

There’s alot more to this challenge than just the CSRF exploit - so I encourage you to read my writeup on it if you would like to learn more about it.

Now, there exists a common technique that helps to prevent CSRF attacks, known as CSRF tokens.

CSRF tokens violate two main paradigms that would typically ensure the success of a CSRF attack: making some aspect of the request parameters in doing a state-changing action unpredictable, and additionally needing more than just the cookie session ID to validate a user.

The tokens are values that which are unpredictable - consider them to be variables like passwords, and thus are only as effective as the number of bits of entropy is high.

CSRF tokens work through being generated from the server, and transmitted back to the client. The client must then include this secret value into their next HTML request back to the server - if that value is malformed or missing, the server rejects the request regardless if that user’s session ID from the cookie was validated in it. The generation of the token can be once per user, or once per new request. Typically, adding this extra level of verification to all state-changing requests are a good way to mitigate any possible CSRF exploits in your application. However, the use of these tokens must also be treated with caution, for they can be trivial to bypass if not implemented correctly.

As an example, consider my other writeup for the challenge “Viper”, also from REDPWNCTF 2020. The premise of that challenge focused mainly on another vulnerability known as cache-poisoning, but at its core, the use of poisoning was a vehicle to deliver a CSRF attack. We wanted to utilize an API endpoint that was only relevant if visited by an admin. The endpoint in question would change the contents of a webpage if it was called. This challenge also employed CSRF tokens that would shut down any basic attempts at unauthorized request making, which were generated by an RNG function. Consider the provided code found in Viper’s infrastructure:

app.get('/analytics', function (req, res) {

const ip_address = req.query.ip_address;

(...)

client.exists(ip_address, function(err, reply) {

if (reply === 1) {

client.incr(ip_address, function(err, reply) {

if(err){

res.status(500).send("Something went wrong");

return;

}

res.status(200).send("Success! " + ip_address + " has visited the site " + reply + " times.");

});

} else {

client.set(ip_address, 1, function(err, reply) {

if(err){

res.status(500).send("Something went wrong");

return;

}

res.status(200).send("Success! " + ip_address + " has visited the site 1 time.");

});

}

});

});

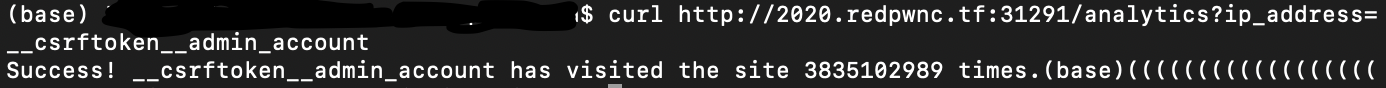

The token in this challenge is a randomly generated number, that is between 10000-1000000000 bits long. There is no efficient way to brute-force its value. That being said, the mishandling of such tokens is one of the vulnerabilities we are meant to exploit in this challenge. Tokens should not be passed around in multiple areas of the infrastructure where it could possibly be leaked. Ideally, you would want your token values to be dynamically generated unique to your user/request, and then discarded afterwards. However, the Viper challenge employed a cache which kept the admin’s CSRF token, which was dynamically changing based on the number of times the admin visited the page, inside it with a trivially easy-to-figure-out cache key("__csrftoken__admin_account"). If you wanted to grab the CSRF token, you just needed to make a request with the correct cache key formatted in your request params to recieve the CSRF token. With this, you could construct a CSRF attack as normal, including the token to bypass that additional check.

curl http://2020.redpwnc.tf:31291/analytics?ip_address=__csrftoken__admin_account

It’s important to guard against CSRF attacks - they’re prolific and yet, despite plenty of security researchers implementing different ways to protect against them, they still pop up. The reason why you shouldn’t click on any suspicious unverified link is due to the possibility that the application the link could be spoofing is vulnerable against CSRF attacks - the webpage you will be directed to could look like my simplified HTML webpage above, with a request constructed behind the scenes and sent to the server with your credentials/validation stamped on it. Once you visit that webpage, you unfortunately wouldn’t be able to do anything to undo or “unsend” that request. CSRF attacks could install applications into your computer without your knowledge via downloading the source online, they could change your email address or rescind privileges from users - if there exists an action that is initiated from an HTTP request, then a CSRF attack can happen from it. Of course, CSRF attacks aren’t the only thing that you’d have to worry about if you click a suspicious link - we still need to worry about Cross-Site Scripting attacks (XSS), but that might be an article for some other time.

Jam