10 minutes

Cryptography and P vs. NP: A Basic Outline

Comic from XKCD.

I am not an expert in either cryptography nor algorithm analysis. However, ever since a very rewarding advanced algorithm analysis class, one question has always dwelled in my mind: what would “P=NP” mean for cryptography? I had heard that such a statement, “P=NP” is controversial in the world of security. Learning about algorithm complexity has certainly shed quite a bit of light on the topic. As a cybersecurity researcher, I was compelled to satisfy my curiosity and answer that question for myself.

I do not consider myself an authority on either algorithm complexity analysis nor cryptography. However, I hope that this quick outline of the important concepts illustrates the severity of “P=NP” in the world of security. If this post could spur other individuals to think about and appreciate the uncertainty of proving such a statement, and appreciate how far we have come in data privacy, then I would be satisfied that I brought this discussion forward.

So, let’s first begin with a few explanations.

What does “P vs. NP” even mean?

For the sake of this article, I won’t be going too in-depth on the definition of P or NP, but I will give a quick rundown here. In computer science, there exist numerous different computing problems that can be grouped into different categories based on the efficiency of their solution (if there exists one). Many problems that we are introduced to as a beginner CS student are all considered “easy” to solve: they have solutions that are verified to have run in O{n^k} (n raised to the power of k) time - polynomial time. Problems such as determining graph-connectivity(BFS), sorting an array(quick sort), or finding an element in an array (binary search) are all considered to be easy problems; they are considered amongst the problems in “P” - polynomial time. The opposite of this are problems that are known to be “hard” - no solution exists that runs in polynomial time. To prove a problem is hard, is to prove that there is, without a doubt, no solution that which is verified to run in polynomial. Therefore, they are considered NOT in “P”.

But, as with everything in life, uncertainty must be accounted for and in the world of applied mathematics and algorithms, how do we group problems that don’t have a polynomial solution yet? The wording I used in the above paragraph is important - problems are hard if it is verified that absolutely no polynomial solution exists. However, it is natural to consider the problems with which we have yet to prove or disprove the existence of a polynomial solution in the first place. This is where the category of “NP” comes in. The travelling salesman problem, the boolean satisfiability problem, the graph-colouring problem. Consider these problems stuck in limbo, where we have yet to really figure out if an efficient solution exists that can solve them. The category “NP” showcases this state of limbo as it encompasses these uncertain problems AND problems in “P”. Do they or do they not have efficient solutions? To consider only the problems in limbo, we group them in their own category of “NP-complete”. Something that is incredibly interesting and fascinating about NP-complete problems is their ability to be reduced into another instance of a different NP-complete problem. This is explained in the celebrated Cook-Levin Theorem, which proves that any problem in NP can be reduced to the boolean satisfiability problem, which itself has been proven to be NP-complete.

Several things require context here.

NP-Completeness

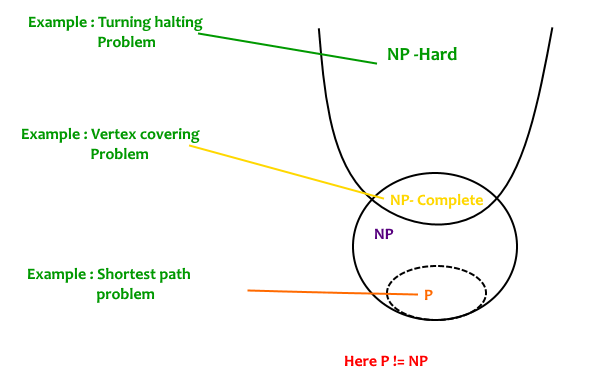

The definition of NP-Completeness that I will be working with is the subset of problems that are formed from the intersection of the subset of NP problems, and NP-Hard problems. The diagram below gives a visual representation of the subset of NP-Complete problems (courtesy of GeeksForGeeks):

NP-Completeness of a problem can be proven using a verifier algorithm that will be given a purported solution of the problem, and apply that solution and validate its correctness (or determine if it isn’t). The verifier algorithm runs in polynomial time.

Reduction

In the study of algorithm and computer science theory, reduction is to take an instance of some challenge, denoted as X, and convert or transform it into an instance of a different challenge, Y, with which we have more information of or know the solution of. As an example, how do you shoot a blue elephant? Use a blue elephant gun. How do you shoot a red one? Paint them blue, then use your blue elephant gun! :)

Cook-Levin Theorem

Simply put, the Cook-Levin Theorem states that the boolean satisfiability problem is NP-Complete.

If we know that all NP-complete problems are reducible to each other, and if we assume that the subset of problems “P” and the subset of problems “NP” are in fact belonging to the same group, then all NP-complete problems can be reduced to a problem that exists in P. Therefore, every NP-complete problem has a solution that can be verified to run in polynomial time. If “P=NP” this is big news. This means that many problems that we have spent years trying to determine an efficient solution for simply needs to be reduced to a problem in P, and solved with a solution that already exists!

If “P!=NP” this is equally important! That means that, all NP-complete problems are, in fact, hard. Therefore, no efficient solution for them exists at all.

Introduction into Cryptography

From my blog, it is clear to see that my expertise lies in web-based exploits and problems. But I am still a student of applied mathematics, and thus cryptography is a field of study that has constantly been on my radar.

Cryptography, in its most generalized form, is the act of encrypting and decrypting data in order to intentionally obfuscate the information to protect the contents of said info. Encryption takes plain-text, then uses a cipher to transform it into cipher-text (more on the method of how it does that later), which can then be decrypted using that same cipher and retransforming the cipher-text back into plain. This is an INCREDIBLY simplified description of cryptography. Crypto is EXTREMELY important to the functions of computer security and digital privacy as we know it. Specifically, crypto serves several purposes:

- encryption, as mentioned before.

- authentication, which validates information from a trusted source.

- integrity, which will ensure that the stream of data will not be altered on its transmission to the destination.

Keys and “Asymmetric” encryption

Dual-Key Cryptography is also called Asymmetric Cryptography. Specifically, it allows for secure communication in a channel between two people. Asymmetric cryptography relies on the use of two keys - parameters that which specify the transformation of plain to cipher, and vice-versa for decoding. It works as so:

- There exist two keys: one is publicly available, and expected to be known by many. The other is private - expected to be known by one.

- Consider a user, Alice, who wishes to send information to another user, Bob. Alice is aware that Bob has a public key that can be used to encrypt data to send to him.

- Alice uses the public key to encrypt some plaintext. She sends the resulting ciphertext to Bob. She cannot decode the ciphertext she has just encrypted with Bob’s public key.

- Bob receives Alice’s ciphertext, and uses his private key to transform it into plaintext. Since his private key is used specifically for the decoding of information that was encrypted by his public key, he is able to do this without much effort.

The idea here is that the two keys aid in the crypto process but serve different functions. The public key encodes, while the private key decodes. The private key is assumed to be known by only one person, so the act of decoding is only capable of being performed by that single individual. However, anyone who knows the public key are free to encode data with it as they wish - keeping in mind that once its in cipher form, it cannot be reverted back to plain without the private key.

The “safety” of asymmetric cryptography relies on just how long it would take to try and brute-force your way into decoding a cipher without the necessary decoding key. There are several measures in place that prevent a malicious hacker from using a few dedicated CPUs to guess the hashes of a given ciphertext. As an example, if you wanted to somehow guess the private key yourself, the existence of information entropy - the average “level” of uncertainty associated to any random variable, in this case the value of the key - will deter you. If you intend to guess the key value (which is often randomized), you will need to overcome the hurdle of the extremely high value of uncertainty in correctly guessing it, so the odds are not in your favor. The bigger size your key, the more information entropy you will have to deal with. Additionally, open-source encryption algorithms are widespread and widely discussed, allowing for the their innovation and improvements as new iterations develop. This means potentially more complex keys, or different encoding algorithms.

Cryptography relies on the simple mathematical principle of one-way functions: it is exceedingly difficult to undo the transformation of a plaintext document to ciphertext without the correct key - and so far, there does not exist any sort of reversing algorithm capable of doing so in an efficient manner, and in a manner that applies to numerous different cryptographic algorithms as well. Reversing the crypto function is “hard” to do…

What if P = NP?

Finally, we can answer the issue here. What are the implications of proving “P=NP” to cryptography?

Consider cryptographic algorithms in the context of a hacker. They are considered to be one-way functions due to the fact that reverse engineering the crypto algorithm will take far too long. In this sense, it is extremely easy to generate ciphertext - the function in question is easy to compute on any input. However, the resulting ciphertext output, the image, is hard to invert - that is, reversing the function to get back the original parameters. Think of it like baking a cake. It is easy to, given all the ingredients, combine the items and pop our mixture in the oven to receive a freshly-baked cake. However, in comparison, it is considerably harder to reverse the baking process and reduce our cake back into its base components of eggs, sugar, flour, etc.

The problem of reversing a cryptographic algorithm - inverting the one-way function of encryption - so far lies amongst the problems in NP-Complete. If we prove that the subset of problems P and the subset of problems NP are one and the same, P=NP, we have inadvertently stated that there does exist a solution that can efficiently/quickly reverse a cryptographic hash - namely, in polynomial time.

P=NP means the end of cryptography as we know it. One-way functions will no longer exist! Strong cryptographic algorithms are only formidable as withstanding the tests of time in the face of hackers brute forcing their ways through them. If P=NP, time will no longer be on our side, and password/data security will be something trivial for a malicious hacker to bypass.

To this end, many operate on the assumption that P != NP, and there exists dedicated research into proving so. For if we end up finding that P = NP, our privacy and online security would crumble right in front of us.

Jam

Further Reading

- “Explained: P vs. NP” Hardesty, Larry. “Explained: P vs. NP.” MIT News, 29 Oct. 2009, news.mit.edu/2009/explainer-pnp.

- “An Overview of Cryptography” Kessler, Gary C. “Overview of Cryptography.” An Overview of Cryptography, 1 June 2020, www.garykessler.net/library/crypto.html.

References

- Rouse, Margaret. “Asymmetric Cryptography (Public Key Cryptography).” SearchSecurity, 20 Mar. 2020, searchsecurity.techtarget.com/definition/asymmetric-cryptography.

- Cook, Stephen. “The Complexity of Theorem-Proving Procedures.” ACM Digital Library, STOC ’71: Proceedings of the third annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, May 1971, dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/800157.805047.

- My informative TAs and professors of my algorithm analysis courses.