14 minutes

MapleCTF UBC ver. Introspective

Jan 21-28 marked the inaugural MapleCTF: UBC version, Maple Bacon’s first CTF to hit the scene.

For our very first, we wanted to keep it local. This made it very different from most other CTFs that one would be used to. We treated this as a beginner event - hoping to introduce the UBC community to the concept, well aware that we would have to cater to varying skill levels.

The CTF in general

The nature of the audience dictated a few design choices for the CTF as a whole:

Challenge difficulty

As mentioned earlier, the UBC version of MapleCTF was projected to be a beginner-friendly event. The main reasoning behind this was to make this CTF an entrypoint for UBC people hesitant to join based on percieved skill level. We (Maple Bacon) were hoping to convince people to get into cybersecurity more. We tried to make sure that our challenges all had some logical way of solving them, which didn’t take too much technical effort - googling was encouraged, and we hoped that people didn’t feel like they needed to know everything to succeed in this event.

At the same time, we still wanted to be creative and create unique challenges which were difficult compared to our accessible ones. While many challenges and ideas were cut, we managed to figure out unique ways to engineer different problems and vulnerable programs.

Teams

Because this was mainly an introductory event with a sprinkling of advanced problems, we needed a way to gently guide beginners into the event past completing all the accessible challenges. Our idea was the notion of “superteams” - 2 larger mega parties that a team of people would affiliate under, and which their points would be aggregated to the mega party’s point total. This would, hopefully, convince even newcomers to try and hack their way through as many problems as they can, and still feel as though they had made a dent on the event; seeing their points added to a super team’s total. We also figured this could allow teams within the same mega party to collaborate with each other and share tips and tricks. This was a success, we saw many teams under the same party give out general hints that helped newcomers learn something new, tackling other problems past what they felt comfortable with.

The mega-party idea will probably not carry over to the international version, since we aren’t as concerned with being beginner-friendly for it. However, should we run another UBC version, we’ll likely flesh this idea out further and see what other new things we can innovate with it.

Organization of the event

Scoring

Scoring was static and the reasoning for that was to not confuse newcomers on their first CTF. We lost alot of granularity with determining challenge difficulty (more on that later), but we figured that having static scores were easier for us to seperate which challenges were “beginner” and which weren’t.

There are limitations to this - the first one, as mentioned before, was the static scoring made quantifying challenge difficulty harder than it should be. I thought one of my challenges was really hard, until I saw that it had a high amount of solves, roughly equal to a few easy-intermediate challenges around. This skewed scoring - I had 2 challenges both worth 400 points, but one had 10 solves while the other had 2.

Another limitation was perception. Perhaps a challenge wasn’t actually as hard as it first comes off - but no one bothered with it since it was stacked at a specific point value. In my experience, I rarely look at point value anymore and concern myself with total amount of solves - but this is based on me trying out a few CTFs and learning that solve count is more accurate than point value (which is a plus for dynamic scoring). Newcomers will not have this same perception right away when looking at a challenge.

Discord

We used discord as the main point of communication between players and organizers. We set teams up with a private team channel so that they could freely discuss their answers among their teammates and @ one of the organizers in there without fear of leaking solutions. This was a bit of overhead for us to deal with as we found that we had hundreds of teams joining in (so hundreds of team channels to sift through), but the overall experience of the private team channels seemed to be satisfactory and we may consider refining the idea should MapleCTF UBC happen again.

Hints

Any challenge marked as “beginner” players were allowed to ask us for hints on. We had 2 specific groups of challenges: the ones you could ask for hints for, and the ones you couldn’t. Hint giving was allowed for this event, again due to the nature of this CTF, and we saw many people utilize it to their advantage. We set a hard boundary and refused to provide any hints for any challenges which didn’t possess the “beginner” tag.

Even though we did our best to provide accessible problems, we still knew people wouldn’t start the CTF on the exact same baseline. Hint giving was another solution to remedy that - we were open on gently guiding players to the solution for certain challenges. Obviously, we also didn’t want this mechanic to be abused to the point where we would walk people through the solution holding their hand, so we still exercised restraint in providing help.

I personally believe that the mechanic worked out - people did ask for help but they definitely solved challenges on their own. We simply saw the hints as a gentle nudge in the right direction for them.

Suffice it to say, we obviously won’t be upholding this hint giving policy for the international version.

The Business Side of Things

MapleCTF UBC had no chance of happening if it wasn’t for the company sponsors, Arista Networks and Teck Resources.

In order to synergize with the needs of the company, we offered our sponsors a chance to collaborate with us on releasing a challenge in MapleCTF which catered to the specific needs or tech stack of their company. We additionally gave the company representatives the ability to discuss themselves and answer any questions - we were able to treat the CTF as a networking event for potential candidates and the company sponsors, allowing both Arista and Teck more benefits from sponsoring us.

You just activated my Project Manager card

When it came down to brass tacks I decided to step to the plate to coordinate the event at a macro level. My expertise in web-based exploits basically guaranteed that I would also have a large role in creating the web problems, so doing that while also managing the event as a whole was such a task that I didn’t think I could complete.

Keep in mind I still had work and school to do alongside planning - observing all of these working parts come together in unison was rewarding, but it took an enormous amount of my attention. For the later months of 2021 I became busy with challenge design, company sponsor interfacing, and other administrative overhead I didn’t expect. Some things that I learned as an event manager:

You’ll get into the habit of chasing people around

Thankfully I have a very responsive team of capable people working alongside me on the CTF, so it wasn’t a huge issue to ask people every now and then to do specific tasks.

But I still had to chase a few people down and ask them to fulfill whatever role they had. Most small spats and issues were resolved quickly and without conflict, although there was still a bit of overhead that came from making sure people did what they were assigned.

Networking

We collaborated with a few executive members from the UBC CSSS, due to the fact that they had a considerable reach over the technical community in our campus. We also reached out to other clubs that we felt would be interested in this event - our ACM/ICPC competitive programming club, for example, is a very strong team with impressive backgrounds in math and algorithms (they’re also very well known in their respective discipline). We advertised with them and also reached out to nwHacks, Western Canada’s largest hackathon, for potential players there. Thankfully, UBC has a thriving technical scene and we took advantage of that for this event.

Ya like emails?

I essentially found myself being the main point of contact for many things regarding the event. I was interfacing with companies, checking in with the challenge authors for up-to-date information on the problems, and also reaching out to the infra team to visualize a timeline for when the services should be up and running. Being a very type A person made things a bit easier to manage as I had a system of time management and was able to incorporate these different tasks and front-facing meetings into my schedule seamlessly. But organization aside, I found that I soon became the person to talk to for anything MapleCTF-related: questions about the challenges, workshops, administrative discussions, company meetings, etc etc. Having these different roles meant I was never truly “off” for MapleCTF: constantly working on and making sure all systems were ok in every department.

Scope creep

This was our first CTF so I was expecting some of our more novel ideas to fall short come the time of the event. At least from my end, plenty of challenge ideas that I had were scrapped for numerous reasons (I didn’t have enough time, the exploit seemed infeasible for the difficulty scope of the event, I just didn’t like the challenge lol, etc etc). There were also several ideas or concepts that we incroporated into the event that were simplified for the sake of KISS. We really did alot for our first CTF, and none of us wanted more work on top of our already stacked schedules.

Infrastructure

Our infrastructure utilized AWS, kubernetes, github actions, CTFd and grafana.

No I don’t know what k8s is and at this point I’m too scared to ask

Utilizing k8s made continuous container deployment easy. The additional k8s kops tool when combined with our AWS infrastructure simplified alot of stuff for us - making challenge deployment quick and easy and also giving us the opportunity to quickly roll out patches or restart deployment in seconds. Our infra guy created a highly scalable solution which could be added to if needed. Thankfully, not too many spats happened throughout the competition so we didn’t have to worry too much about the whole thing going down.

AWS EC2, very cool

We used mid-size AWS EC2 vms in order to host our challenges. We had a running total of 56 challenges, with about 40 of them requiring containerizing on our infra. Thankfully, we had no issues with dockerizing our challenges and it was the easiest container service to get into.

Our vms were split up by category: rev/pwn, web, crypto. We decided to categorize the vms this way since it made the most sense to us, and allowed us to scale the vms depending on the needs of the category. Web, for example, were simplistic in nature and didn’t really need a hefty amount of compute for. This could change come the international version, but overall we allowed ourselves to be generous in this category but found that we didn’t necessarily need to be.

Challenge design

Short writeups/solutions to my web problems can be found here.

Web Bacon

It was a bit hard to create a series of ramp-up challenges for web since the sorts of things you can do in this field were broad. I decided to at least create a few challenges which would logically follow after one another based on a specific exploit: XSS, and that seemed to be succesful. The largest issue I had with my challenges was a matter of understanding if certain challenges were actually easy or not - a specific problem that I envisioned, “Poem Me”, had far fewer solves than anticipated. While I had people test the challenges out before they made it into production, there was still an inherent bias that the QA had because they at least had seen a couple CTFs beforehand. They had a frame of reference - but how did my challenge look to those without one?

I made alot of design choices to try and simplify the web problems to a level where I felt people could hack at them, have fun, and gain something out of the experience. I knew that engineering difficulty was already a complex thing to do, and doing something like forcing a player to guess what the vulnerability was for a challenge was definitely not my intended strategy. In fact, I had hoped that guesswork would be kept to a minimum when it came to challenge-making.

I truly believe that in the real world, there is an amount of intuition and inference that you would need to make which may or may not completely follow from the trains of thought that a CTF would lead you down - in some cases, I feel it’s inevitable. However, I didn’t want to really teach people how to guess - I wanted to teach people how to correctly audit a security bug and showcase their skills in exploiting it. I felt as though that there were 2 different lessons one could teach and I wasn’t all that concerned with teaching the former.

In some cases, I tried to make things obvious or nudge players towards the solution through certain things (comments in code, using really old versions of libraries, etc etc). However, I felt as though some of my mid-level challenges were not truly intermediate in percieved difficulty.

Valentina, for example, could be solved by looking at the library version of one of its packages, and formulating an exploit from there. But this was a novel approach for some, accounting for the low solves in the challenge.

Will this be an issue for the international version? I’m not sure. I will have more freedom to exercise my creativity over the types of challenges I’ll make - which could mean more difficult challenges, but perhaps the main issue with difficulty just came down to the scoring. Due to how we made scoring static as to simplify the meta of the CTF for newcomers, it meant I had to just hope that my guess at the score value was equally matched with the subjective difficulty of the challenge I made. I imagine that with dynamic scoring, much of the granularity involved with challenge difficulty will sort itself out.

Misc Bacon

I created 3 jail challenges based on Python. Lesson here? Jails are hard to make - in the sense that the number of unintended solutions that could come up is astounding. The jails were the challenges that had multiple flavours of solutions to them, contributing to a higher than normal solve count, and skewing the score values. Pyjail 2, for example, was worth the same amount of points as Valentina 1, but Valentina had about 30% of the solve numbers in Pyjail 2.

Admittedly I was somewhat expecting a few unintended solutions but my mistake was in assuming that not many people would get creative - many people did, in fact, get very creative and found a bunch of different ways to bypass the blacklists in my jail problems. I’m not upset at any one of them - in fact, the novel solutions I saw some people come up with were truly unique and incredible. This was, however, a point against me as I wasn’t fully expecting the different solutions.

A few people did mention to me that they liked the pyjail problems, so I think next time I do a jail problem I’ll score it lower (or dynamically).

Lessons Learned

While I still believe that the justification for a static scoring system was valid, I also believe that dynamic scoring is far easier to deal with and helps to avoid situations where I overestimate and underestimate the difficulty of my challenges - both situations which happened in MapleCTF. While I managed to avoid the misjudgement for all my challenges (only 1 seemed to be easier than I thought, and a different 1 seemed harder than I thought), I’d like to avoid any situations where the scores could be skewed based on point values of challenges completed. For that, I believe that dynamic scoring would be the way to go to remedy this.

Additionally, it helps to be more generous in the distribution of tasks. Early on I had adopted much of the responsibilities myself and while I won’t deny the small part of me that likes the thrill of completing every task on her own, I also won’t deny the tremendous overhead I experienced when I decided to put more on my plate than I could finish.

Stats

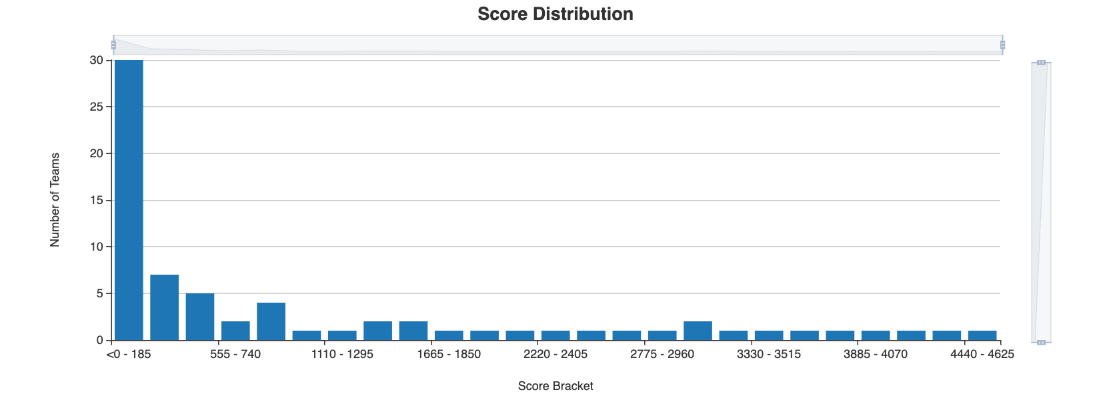

Our score distribution was pretty much skewed to the left, as we somewhat expected:

Most people solved a few of the beginner challenges and decided to stop there.

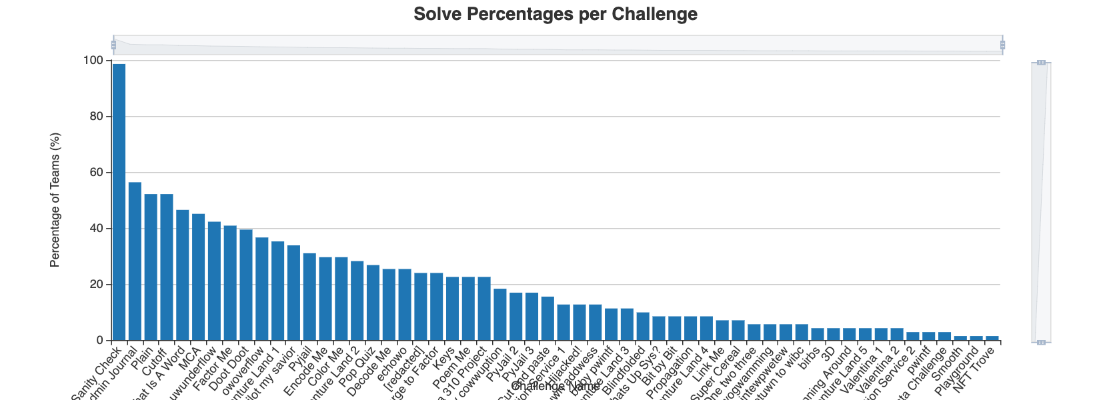

When it came to the individual challenges:

Our beginner challenges all had solve counts close together - our harder challenges only had 1-3 solves.

Wrapping it up

MapleCTF UBC was a huge undertaking that I definitely couldn’t have done without my team. It was a massively rewarding event which helped developed my own skills as both a CTF player and software engineer, and I hope to utilize these skills with the lessons learned to create a great international version that all can hack away and enjoy.