4 minutes

RaRCTF 2021: MAAS 2 + Unintended Solutions

MAAS 2 // Notes

Source was the same from MAAS 1 (and will be the same for MAAS 3). MAAS 2 involved the ‘notes’ part of MAAS, where you are prompted to register a user and afterwards add key:val attributes to yourself, give yourself a bio, or transfer key:value attributes to another user.

The provided source has some interesting code:

notes/app.py

@app.route('/useraction', methods=["POST"])

def useraction():

mode = request.form.get("mode")

username = request.form.get("username")

if mode == "register":

r = requests.get('http://redis_userdata:5000/adduser')

port = int(r.text)

red = redis.Redis(host="redis_users")

red.set(username, port)

return ""

elif mode == "adddata":

red = redis.Redis(host="redis_users")

port = red.get(username).decode()

requests.post(f"http://redis_userdata:5000/putuser/{port}", json={

request.form.get("key"): request.form.get("value")

})

return ""

elif mode == "getdata":

red = redis.Redis(host="redis_users")

port = red.get(username).decode()

r = requests.get(f"http://redis_userdata:5000/getuser/{port}")

return jsonify(r.json())

elif mode == "bioadd":

bio = request.form.get("bio")

bio.replace(".", "").replace("_", "").\

replace("{", "").replace("}", "").\

replace("(", "").replace(")", "").\

replace("|", "")

bio = re.sub(r'\[\[([^\[\]]+)\]\]', r'{{data["\g<1>"]}}', bio)

red = redis.Redis(host="redis_users")

port = red.get(username).decode()

requests.post(f"http://redis_userdata:5000/bio/{port}", json={

"bio": bio

})

return ""

elif mode == "bioget":

red = redis.Redis(host="redis_users")

port = red.get(username).decode()

r = requests.get(f"http://redis_userdata:5000/bio/{port}")

return r.text

elif mode == "keytransfer":

red = redis.Redis(host="redis_users")

port = red.get(username).decode()

red2 = redis.Redis(host="redis_userdata",

port=int(port))

red2.migrate(request.form.get("host"),

request.form.get("port"),

[request.form.get("key")],

0, 1000,

copy=True, replace=True)

return ""

@app.route("/render", methods=["POST"])

def render_bio():

data = request.json.get('data')

if data is None:

data = {}

return render_template_string(request.json.get('bio'), data=data)

The relevant parts are when mode is equal to bioadd. There’s a pretty hefty sanitizer in play that removes all relevant characters required for an SSTI. This is further supplemented by the endpoint to /render, which takes your input and passes it into render_template_string. TL;DR: Server-Side Template Injection involves injecting code into template expressions that are evaluated on the server. Essentially, if you have an app vulnerable to SSTI, then you should be able to inject any expression into {{double curly brackets}} and that expression would be evaluated.

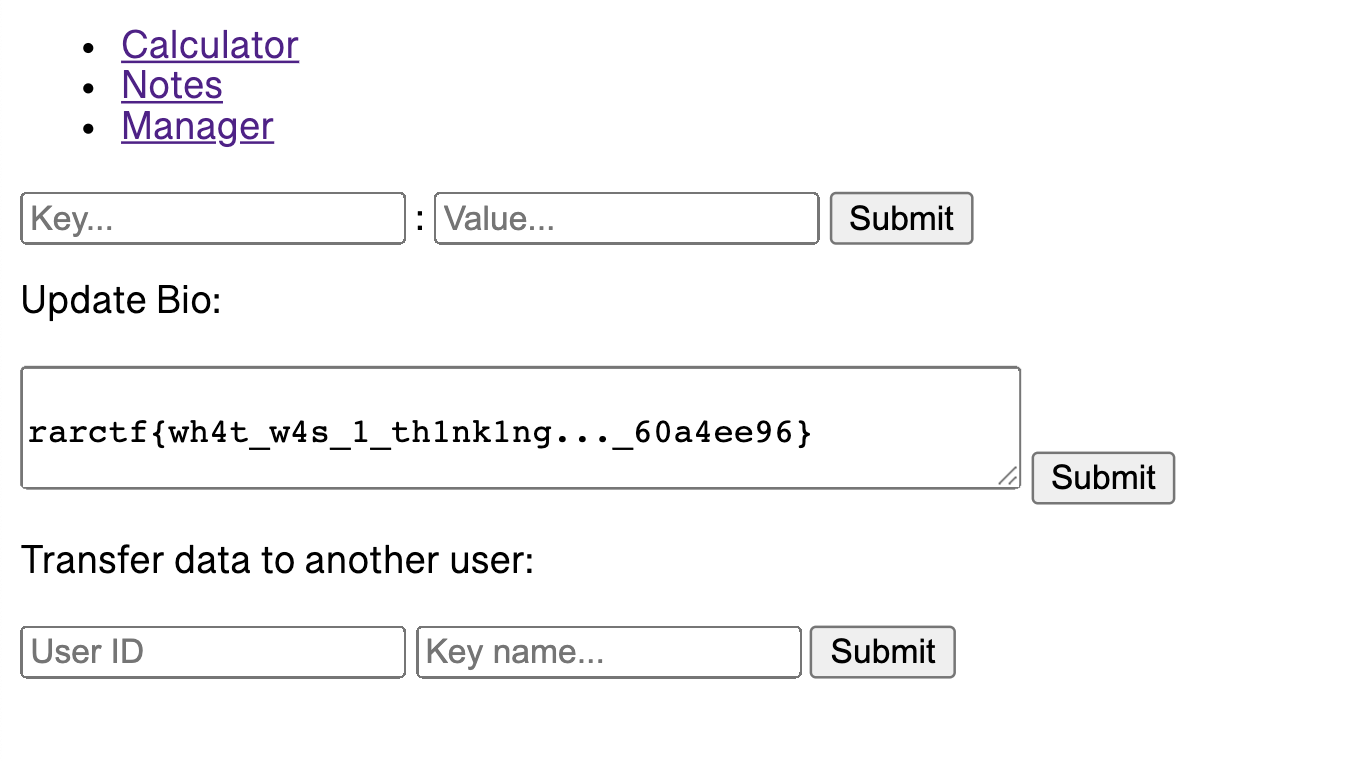

But, this is a sanitizer function, and it does specifically remove the {} characters, so we would be out of luck for SSTI. Out of sanity, I double checked that {{template expressions}} were disallowed and tried a basic SSTI payload such as {{7*7}}.

Oh, wait a second. The sanitization filter isn’t actually applied to our input! We get a quick and easy SSTI vulnerability.

We can modify our payload from the previous MAAS 1 to better suit a template expression:

{{request.application.__globals__.__builtins__.open('../flag.txt','r').read(-1)}}

Update your bio as this and the flag will be loaded for you!

While this is the unintended solution, the intended one did involve throwing an SSTI payload over “behind” the filtering by manipulating the redis container that would contain the user objects.

If the filter was actually applied, you would be forced to instead leverage the application’s key transfer feature to force a key-transfer connection to a Redis container at port 6379 - which is the defualt port of the Redis server.

The code for the keytransfer actually calls the Redis command “migrate”:

elif mode == "keytransfer":

red = redis.Redis(host="redis_users")

port = red.get(username).decode()

red2 = redis.Redis(host="redis_userdata",

port=int(port))

red2.migrate(request.form.get("host"),

request.form.get("port"),

[request.form.get("key")],

0, 1000,

copy=True, replace=True)

return ""

And we can provide as a port argument the value 6379 to tell the Redis-cli server that the provided “host” argument should have their value changed to the “key” argument. Here, you would then be able to set a user’s port as some arbitrary value that you can control, such as “../bio”. Get 2 users, perform a key transfer to the Redis-server to change one user’s port to “../bio”, and then perform another key transfer to give a “key” called “bio” with the value being your SSTI payload, to the original user. The result after all these Redis manipulations should be the execution of your SSTI payload that would have completely avoided the filtering.

You could, additionally, use your previous payload from MAAS 1 and take advantage of the challenge’s improper network isolation issues to make internal calls to the MAAS 2 notes API. This was possible due to the fact that MAAS 1-3 were 3 different, linked docker containers that (unintended by the dev) could be interacted with from between docker containers. This “sharing” feature allowed you to reuse an attack vector in one challenge to request for resources from another challenge, like their flag. This could be done for any of the MAAS challenges. Interesting stuff!

RaRCTF was a good CTF, and given how it appears to be team WinRaR’s first CTF, I’m thoroughly impressed by the quality of the challenges.

Vie