7 minutes

justCTF[*] 2020 - A Collection of Web Problems

This last weekend was justCTF 2020 (delayed last year so it was held this year :P), held by justCatTheFish. Although I was focused between this and some other work, I was able to look through a few of the web challenges and will document them here.

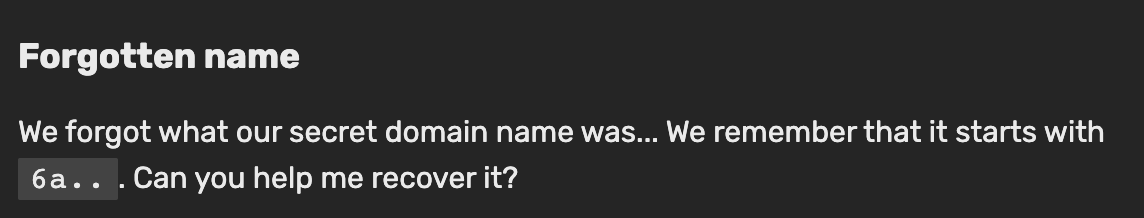

Forgotten Name

I found this on a total fluke. I wasn’t paying attention to the challenge much but the description was compelling:

I’m hesitant to attempt to nmap all known domains of justCatTheFish’s network, and so instead thought about the nature of their subdomains. Every other challenge that required accessing a server was suffixed with the subdomain *.jctf.pro. I decided to search through certificate transparency logs with that subdomain to see what would come up, and a certain URL caught my eye: 6a7573744354467b633372545f6c34616b735f6f3070737d.web.jctf.pro/. It had the correct beginning characters and it ended in jctf.pro, and visiting it we see a small message: “OH! You found it! Thank you <3”.

So, the secret domain has been found. Hex decoding the mash of numbers in the URL gave the flag: justCTF{c3rT_l4aks_o0ps}.

Computeration

This challenge was labelled as hard but it had an unintended solution. The challenge featured a note repository and the ability to report URLs to admins - basic XSS stuff. However, the notes were stored in our browser’s localStorage, which is unique per domain and session, and likely doesn’t involve cookies due to this. Looking at this, my first thought came to XS-leaks (a web vulnerability I’m currently studying and researching), which would essentially side-channel attack a user in their browser to leak information based on functionality and logic of the program.

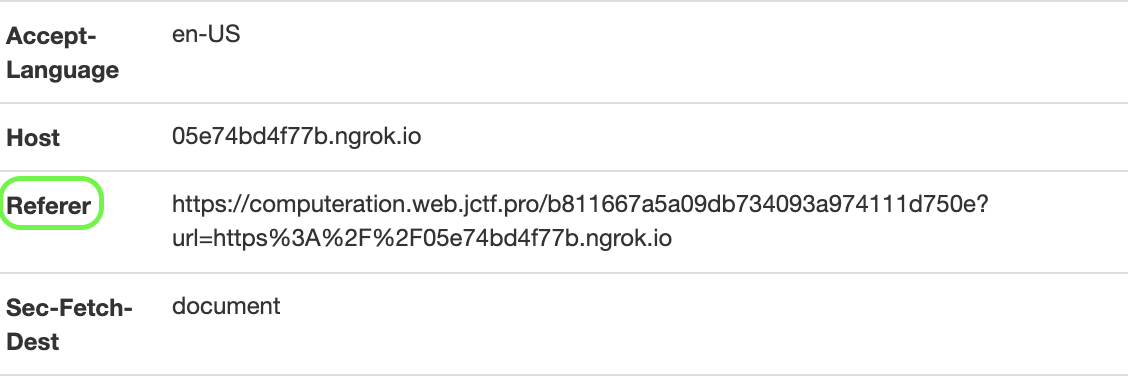

During recon, I spun up a quick server and gave the URL to the bot to check out. When they made the request, I inspected the headers:

I don’t typically see the referer header in many requests, because there are inherent security concerns with using it. Out of curiosity I tried to access the referer site myself, and unintentionally got the flag that way.

The key is in the response headers I recieved after visiting the domain. Their referrer-policy header was set to no-referer, which is a mispelling of no-referrer. Confusingly, the referer request header is misspelled - which is a different story. When the admin bot begins to fire a request to a URL we specify, its domain’s referrer-policy will be set to unsafe-url since no-referer technically doesn’t match any of its options. Therefore, the referer request header is added to the bot’s GET request to our URL.

Although unintended, still a good discussion on the security of referrer headers. Looking at the flag also validated my suspicions of this challenge’s intended solution requiring XS-leaks.

Baby-CSP

I was primarily focused on this challenge. We see some interesting PHP code right away upon visiting it:

<?php

require_once("secrets.php");

$nonce = random_bytes(8);

if(isset($_GET['flag'])){

if(isAdmin()){

header('X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff');

header('X-Frame-Options: DENY');

header('Content-type: text/html; charset=UTF-8');

echo $flag;

die();

}

else{

echo "You are not an admin!";

die();

}

}

for($i=0; $i<10; $i++){

if(isset($_GET['alg'])){

$_nonce = hash($_GET['alg'], $nonce);

if($_nonce){

$nonce = $_nonce;

continue;

}

}

$nonce = md5($nonce);

}

if(isset($_GET['user']) && strlen($_GET['user']) <= 23) {

header("content-security-policy: default-src 'none'; style-src 'nonce-$nonce'; script-src 'nonce-$nonce'");

echo <<<EOT

<script nonce='$nonce'>

setInterval(

()=>user.style.color=Math.random()<0.3?'red':'black'

,100);

</script>

<center><h1> Hello <span id='user'>{$_GET['user']}</span>!!</h1>

<p>Click <a href="?flag">here</a> to get a flag!</p>

EOT;

}else{

show_source(__FILE__);

}

// Found a bug? We want to hear from you! /bugbounty.php

// Check /Dockerfile

There’s a reflected-XSS attack which can be done through the user query parameter. However, the Content-Security-Policy is pretty strict and my XSS payload has to be less than 23 chars. The CSP uses a nonce value (randomized 8 bytes), which we can see in the for loop above, is hashed 10 times. There’s no feasible way to reverse a hash 10 times. So, there are 2 obstacles to overcome: how to create an XSS payload that’s at most 23 characters long, and also how to bypass the hashing of this nonce value.

The nonce value and PHP response buffers

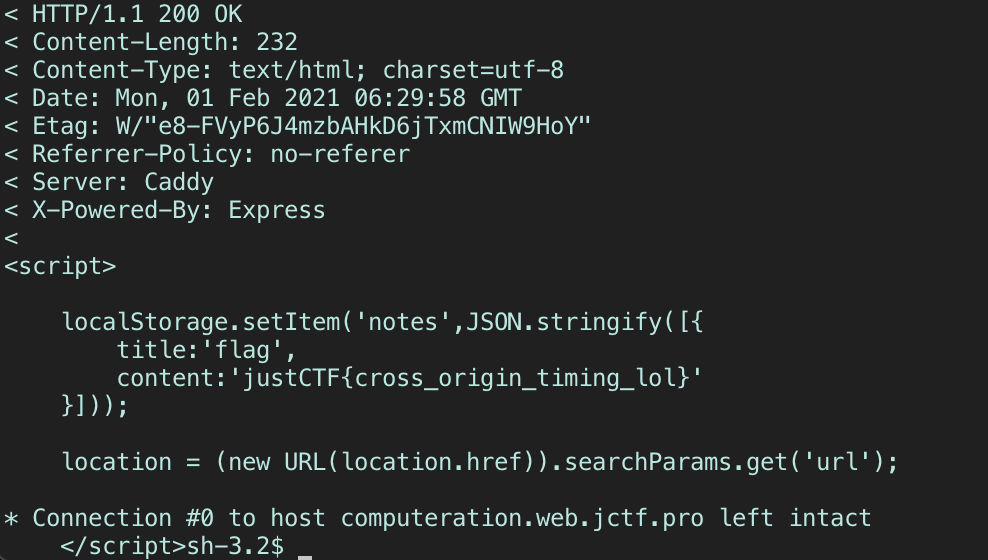

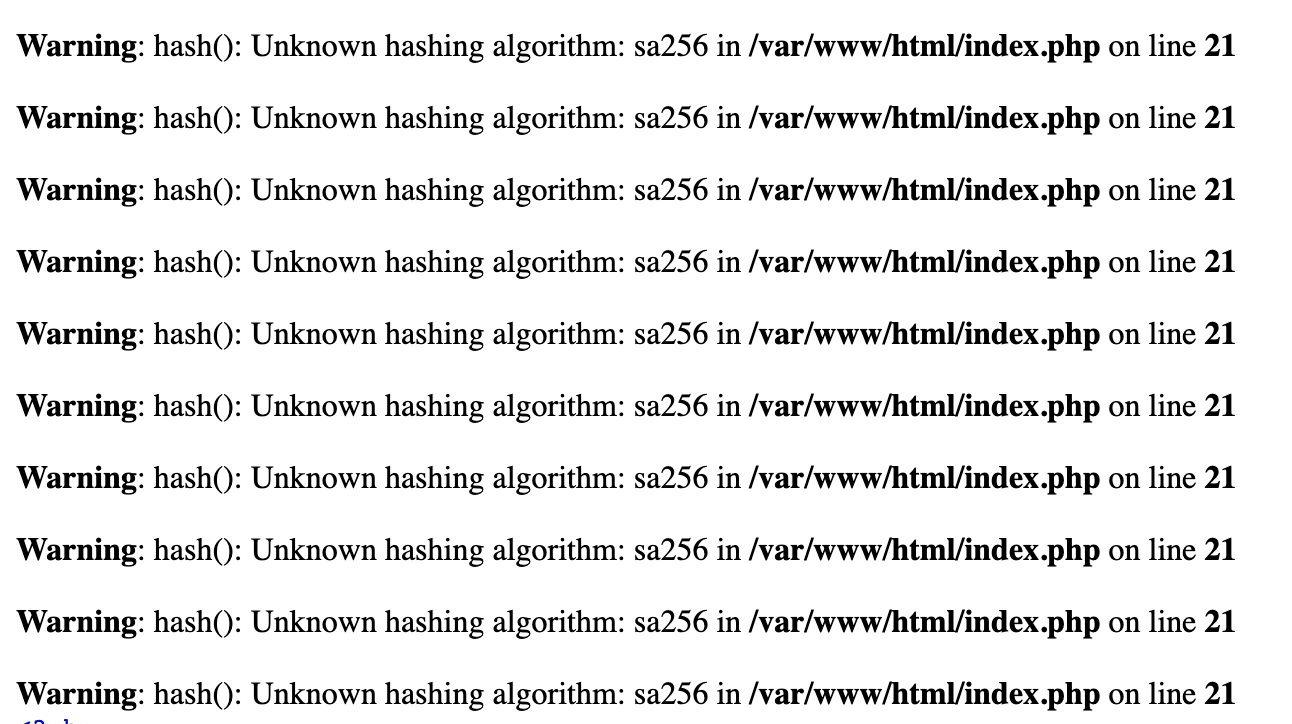

The nonce value is hashed 10 times with a hashing algorithm of our choosing (md5 if we don’t choose), using the alg query parameter. However, something interesting that teammate Filip pointed out while I was working on this challenge was the fact that this server was being run on a development config, which you can find out by checking the /Dockerfile endpoint. This fact became relevant to me when, in doing recon for the challenge, I tried to make a GET request with the alg query parameter and accidentally misspelled sha256 (it was 3am). What happened was this:

We get 10 warnings (A warning per iteration in the for loop) that fill the webpage, complaining about our mistake. The reason why we see these is because the PHP server is in a development environment - so the warnings are given to us in the responses.

PHP was initially developed as a procedural language. The script provided to us is executed in order - it first does actions according to the presence of a flag in a recieved request, then it iterates through the for loop, hashing the nonce value accordingly. Then, it performs actions based on the presence of the user parameter. It is here in the if statement for the user query where the Content-Security-Policy is set:

header("content-security-policy: default-src 'none'; style-src 'nonce-$nonce'; script-src 'nonce-$nonce'");

So headers are being modified when the user query is specified, but if you also specify an alg query and give it an invalid value, the server’s response will first have 10 warnings before the headers of that response are ready.

These warnings also reflect our input back to us, so we can modify the size of each warning by our alg input. Why is this relevant?

PHP has a mechanism called output buffering - if you have a script that began outputting data before the headers were set, that data is put into a buffer which will be sent once the entire response is ready. The PHP response buffer is 4096 bytes (4KB), and once it’s filled, it’s immediately flushed and the data within it is sent over.

So, if we could specify a value in the alg query that’s sufficiently long enough to fill the response buffer, we will initiate a response sent from the server, regardless of whether or not the headers are ready. Thus, the CSP header() call will be ignored as a response was already sent. With this, we don’t need to worry about whatever the $nonce value is hashed to, cause we can bypass the CSP entirely.

XSS payload <= 23

I initially tried to format an xss payload on my own, trying to shorten my URL domain or use different tags, but with some googling I found <svg/onload=> to be effective.

Specifically, the example provided was <svg/onload=eval(name)>, so ideally I could modify the name variable to do what I want. Something like:

name = alert(1);

<svg/onload=eval(name)>

Putting it all together

We can test out if whether or not overloading the response buffer will bypass the CSP with this query:

https://baby-csp.web.jctf.pro/?alg=aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa&user=<svg/onload=alert(1)>

And this will prompt an alert. We can see the HTML of the webpage and find that our <svg> payload is correctly interpreted as such:

So, all that’s left is to craft a working payload. Due to the /bugbounty.php endpoint, we have a way to make the admin visit a URL we specify, so the rest of the problem is correctly formatting our XSS payload. I ended up hosting a page on my server to redirect the bot to the flag endpoint once they visited, and leak the contents of that response to a webhook. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to grab the flag in time before I could submit it - at that point, the CTF had ended :( I suppose next time I’ll be more efficient given that I learned alot about PHP.

And that’s a portion of the challenges I took a look at during justCTF. Hopefully next time I can solve challenges more efficiently :P

Vie